The tech-led future of social care post COVID-19

As we have discussed previously, the social care sector in the UK is staring into an abyss of shrinking care capacity and exponentially rising demand. We know many of the contributing factors to this – chronic underfunding, a lack of collaboration, a workforce crisis and a lack of modernisation, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic […]

As we have discussed previously, the social care sector in the UK is staring into an abyss of shrinking care capacity and exponentially rising demand. We know many of the contributing factors to this – chronic underfunding, a lack of collaboration, a workforce crisis and a lack of modernisation, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic – all of which are testing social care to the limits.

As we emerge from the spectre of the pandemic and look to reset how social care is delivered, I believe we can actually use the pandemic as a positive. As I discuss in this report, the sector has an opportunity – at all levels – to reassess, redesign and re-ignite a strategy for lasting, effective change.

Technology should, of course, be at the heart of this change. The pandemic saw many social care organisations move services such as assessments, care planning, reviews and outreach to a digital environment at astonishing pace. This is momentum we should harness. Indeed, many people I speak to in the social care sector agree that we are at a digital tipping point; an apex leading to much faster spread and uptake of new technology and online working.

Watch as Steve Morgan explains why COVID-19 is a positive for social care transformation.

In this report I take a look at the main challenges I see for the future of social care, call for a long-term plan that will address these issues head on, and detail the critical technologies that will, I predict, be transformative in building a system that is financially sustainable, puts people at the heart of activity and supports the brilliant social care workforce.

The Challenges of Future Care Delivery

1.Income and expenditure

Looking at the future of care, and realistically I think you’ve got to be looking beyond 2023, the biggest challenge undoubtedly has to be austerity.

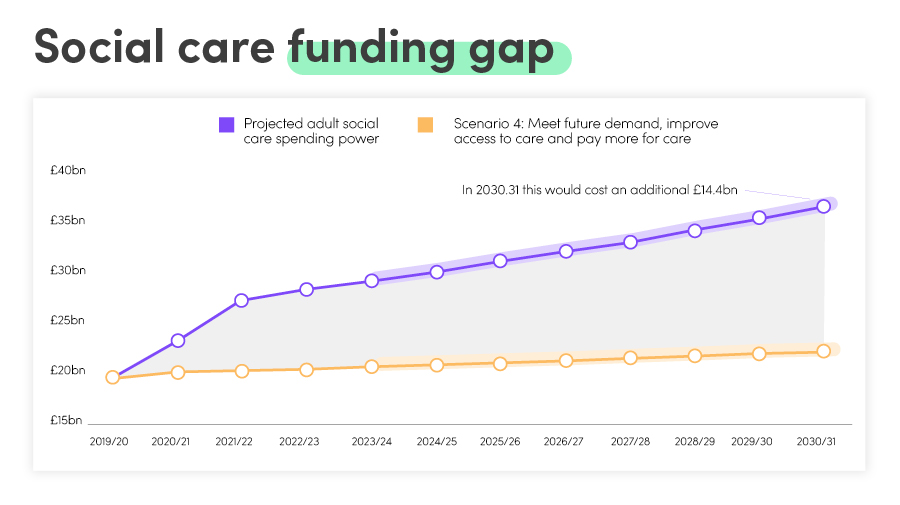

Much has been published on this topic, so I’m not going to dwell for very long on it, but this recent analysis from The Health Foundation is worth sharing. It explores what it would cost to fix the crisis in adult social care in England, including stabilising the current system, improving access to care and providing social protection against care costs.

What’s more, the response to COVID-19 hasn’t been cheap and measures must be taken to manage the economy.

Councils have already put the 3% adult social care precept into council tax, but this will not meet the rising demand and so other options need to be seriously looked at. A 1% increase in Income Tax or National Insurance Contributions is one option that will deliver €6-7bn of additional funding, but arguably the issue with this option is that we don’t know what the working population is going to be following the pandemic. Just what will the economic impact be? What levels of unemployment will we have?

In one of the earlier papers in this series (link to Rethinking health and social care post Covid-19), I talked about how staffing is far and away the biggest cost to the care sector. The latest 2.2% increase in National Living Wage is going to heap further pressure on the 12,000 private providers of care in the UK. When 90% plus of your cost base is people, even small wage increases eat into already fragile margins.

This means local authorities will simply have to pay more for the delivery of care. Private providers are already struggling, and they can’t reduce their cost base any further. Experience shows (it’s also common sense) that the quality of care being delivered is directly proportional to the amount local authorities pay for it. At a time when local government is already stretched by years of reduced central funding, and loss of revenue because of COVID-19, this will be tough – and detrimental to other council services.

Several comprehensive reviews have explored what funding options are available; what is now needed is a decision on how social care will be funded, and a timetable for implementing this.

2.Fewer private providers

Over the next six to twelve months, the number of private providers will shrink drastically. This, I predict, will lead to some of the major players growing their base to give themselves some chance of using economies of scale to drive down the cost of delivery just to maintain margins.

Smaller care delivery organisations cannot invest in themselves to drive efficiency. At the same time, they’re at capacity just delivering day-to-day care to be able to invest in technology that can play a part in making the delivery of care more efficient. Therefore, you can argue there’s an opportunity in this scenario, although it’ll be tough in the short term.

3.People and processes

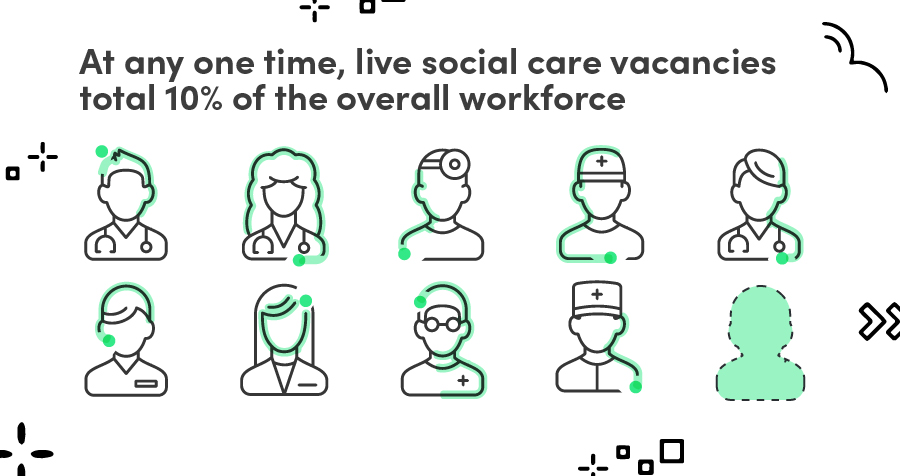

The social care workforce is in a dire need of investment and reform. Currently, Skills for Care estimates that there is a 30.8 per cent turnover rate, equivalent to approximately 440,000 leavers over the year. That simply isn’t viable. There are also an average of 122,000 social care vacancies at any one time. That’s substantial given the sector employs around 1.5 million people in England.

There’s no question that the average age of care staff – especially those delivering care – is growing rapidly. Over the last year, with negative press coverage around pay, working conditions and infections in care settings, this already unappealing profession has taken a further hit.

At the same time – and I’m aware there are exceptions – the care industry won’t naturally look to exploit technology to help in daily roles. This raises the need, over the coming years, for the sector to question how it can make the delivery of care more palatable, and therefore deliver a career that people choose to go into.

This must be balanced against making the sector accessible. A big attraction of care work is the lack of barriers to the profession. Contrast that to nursing; all too often you must now go in as a graduate, which brings everything along with it, including debt and lost years of work. Yes, nursing salaries have improved over recent years (there’s clearly another discussion around the latest pay award), but you wouldn’t say that anybody is going to make their first million from the profession!

Then there’s the issue of esteem. Whilst some efforts have been made during the pandemic to increase the recognition of people working in social care, care work lags well behind the NHS in terms of pay, conditions, career opportunities and access to training and development. I wholeheartedly agree with ADASS, who said in a recent report: “For too long the skilled and compassionate adult social care workforce has been undervalued by the rest of society.”

As we move steadily towards a more integrated health and social care system, there’s an opportunity to start planning now for how we build a workforce which is better placed to work closer together and provide more multi-disciplinary and coordinated care to people. There could also be the opportunity for more join roles and join qualifications, enhanced by technology such as decision support tools, assessment tools and so on.

If we fast forward to 2025, will greater use of technology, that transforms how we deliver care, reduce pressures on staff and free up resources improve the situation? I firmly believe the answer is yes.

4.Old-school thinking

I firmly believe that social care delivery is fixed in the 19th Century. In so many cases it hasn’t made it to the 20th Century, let alone the 21st!

What’s holding back modernisation, aside from the challenges discussed above, is the lack of investment in shifting focus away from remedial and acute services, towards community-centred preventative models of care, support, housing and technology. A good example is citizens taking the lead on the management of their own wellbeing.

The sector is not yet investing a sufficient proportion of expenditure on prevention. In the context of fiscal austerity and rising demand, the capacity of local authorities to focus on the strategies that support people to stay independent and well for longer have been leaving eroded, leaving little choice but to fund services that support people who have priority needs. We need a clear and overriding strategy that once and for all makes prevention a priority; reducing demand over time for acute and remedial services, whilst dramatically improving the quality of lives of many more people.

Although we will always need forms of care ((such as care homes) which support people who require intensive forms of care or support people experiencing a crisis, we do not currently invest enough in models of care that are proven to maintain people’s resilience, wellbeing, independence, and ability to return to their previous state. The shape of wellbeing isn’t a downwards spiral; it’s a spectrum on which people travel backwards and forwards.

The need for a strategic view

The social care system is complex and fragmented, with care being provided by around 18,500 organisations working in 39,000 locations across England. Good practice being developed in one part of the care sector is difficult to share easily with another part.

It’s clear therefore, given the extensive challenges faced, that a joined-up, multi-agency, holistic view is needed if we are to achieve a positive, co-produced, vision for social care. We need a plan that permeates all aspects of sector reform. In the short-term, there’s an urgent need to address the funding pressures, and it can be argued that more needs to be done to drive leadership in social care that focuses on an asset-based, co-production programme of transformation. The development of the ICS structure may be the catalyst for this.

This needs to be allied to longer-term thought processes, because the big questions aren’t ones we can answer this year, or maybe even next. We need to think about the impact of unemployment rising by 5 or 10%. What does that mean for the economy? What does that mean for public spending? What about footfall to already struggling town centres because of the rise of home working? These all impact on the financial abilities of the local authority and more importantly on social interactions – leading back to the problems of isolation and mental health that I discussed in my previous paper.

By thinking long-term and bringing together the fragmented sector, funding decisions can be made for the good of the whole sector – and arguably help that money to stretch further. If this can be used to drive efficiencies and modernise the traditional, very labour-oriented service, then progress can be made. If the sector is viewed as one that invests in technology, innovation and its people, you will attract a cohort of people outside of those people who already do so because they genuinely want to care for people.

Demand for care is not going to reduce, so something has to change – and I think technology is at the heart of lasting, meaningful transformation.

Watch this video as Steve Morgan explains how we can achieve strategic thinking across social care.

Technologies leading the charge

At the time of writing, as the COVID-19 vaccination programme has gathered momentum and thoughts are turning to the post-pandemic world, an unprecedented number of local authorities have contacted Educatief Software Collectief to talk about technology care solutions. They all have one question in common: what technologies can improve the quality of service and reduce the cost?

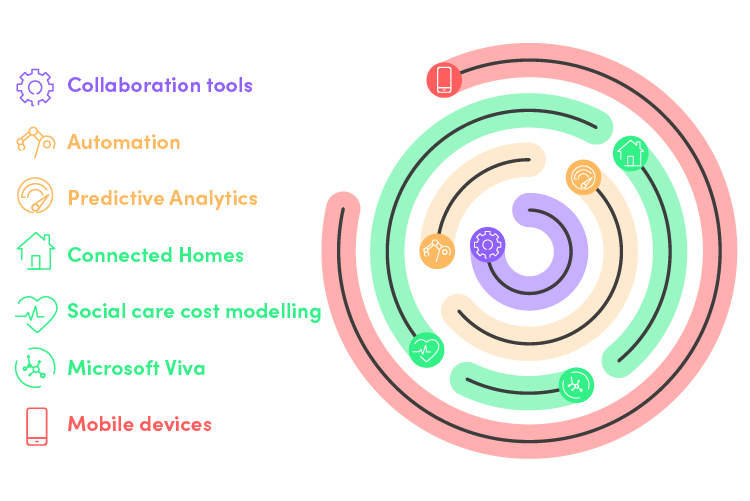

Here are the critical technologies that I think can transform the future of care:

Collaboration tools

Whether specialist videos devices, or consumer technology such as Amazon’s Alexa, anything that allows you to make remote contact with individuals in a far more efficient manner than driving from house-to-house is welcome.

Educatief Software Collectiefis seeing a growing movement towards a ‘delivery ecosystem’. Depending on what the needs of an individual might be, you can plug in different sensors and monitoring capabilities into a connectivity hub, which enables everything from telehealth and telecare to social inclusion and family contact, without having six or seven different boxes plugged in and connected around the house.

Automation

Whether it be a Carelink service, a local authority contact centre or a charitable organisation that’s helping with the care provision, it requires a fundamental change to switch from an inbound telephony-based contact service to a proactive outbound one, where video is part of the contact mix. It is a wholly different service. If you’re going to make those services more productive, you’ve got to reduce inbound demand.

That’s where RPA, AI and machine learning each play an integral part. If the repeatable, mundane demand and everyday tasks are looked after through automation, rather than humans, you create time for people to do the work that makes a difference to them and the people they care for.

Predictive Analytis

Data is critical to any strategic, joined-up future of care. The sector needs to question how it can effectively capture data and then use it in multiple ways, not least to predict demand.

It’s obvious that you really need to keep people at home for as long as possible, given the cost of acute or residential care. By using predictive analytics to understand when somebody is in danger of presenting into health or residential care, you can dramatically reduce the overall cost of care delivery.

The work Educatief Software Collectief did in Barking and Dagenham to predict when somebody would present as homeless demonstrates how the use of data mining and access to the information can make a big difference. If you can predict what the right intervention is at the right time, you have a hugely powerful tool. Using data to inform more effective decisions is the way forward and it will be interesting to see how the rise of the Integrated Care System (ICS) brings together data collection and joined-up data usage.

Connected homes

Housing is a key area to driving modern social care. When we look to the future, there needs to be some fundamental differences made to housing stock. Technology can identify when there are issues with damp, carbon dioxide or humidity. Inexpensive sensors can measure temperature, allowing identification of households suffering fuel poverty. By ensuring knowledge of the environment vulnerable people are living in, you reduce or even remove any knock-on effects.

We’ve seen some good innovation developed on the back of smart meter networks too, where behaviour can be monitored simply through energy consumption. When exceptions are identified – often through automation – intervention can be put into motion.

Social care cost modelling

Social care makes up a majority of local authority spend. In 2018/19, total expenditure on social care by councils was €22.2bn. During the same period, 82% of local authorities overspent against their children’s social care budget, while in adult social care this figure was 47%. Using data to predict outcomes and effective routes forward, social care cost modelling enables users to take any cohort of children or adults and apply one or more of a huge range of potential scenarios to it, showing authorities how much social care services are costing them, and what they can do about it, accelerating the shift away from a more reactive approach.

Microsoft Viva

Employee Experience platforms, notably Microsoft’s new Viva solution, are a vital digital tool as remote working becomes a permanent part of working life. There’s a need to manage work/life balance and wellbeing and the transition to remote-first raises a crucial question: how does an organisation create a culture, a sense of belonging, a mission and connection in the absence of a physical presence. Products such as Viva focus on employee wellbeing to help avoid burnout, highlight efficiency gains and being knowledge and information together in one place.

Mobile devices

The use of mobile technology and improved connection speeds will enable quick access to information across the care system and empower care professionals to work from any base. Providing frontline staff with mobile remote working solutions, encompassing appropriate software and client information, show allow professionals to spend more time with their clients, as well as speeding up data capture, decision-making processes and reducing transcribing errors.

Betamax versus VHS

What we need to avoid is another VHS versus Betamax technology debate. There are numerous products and standards – and so many ways to put the options together – that need to be formally and consistently standardised. Both in terms of technology connectivity, and the data that sits at the heart of it.

I would be disappointed if those standards were simply driven by the biggest people in the market, who become the standard bearers simply because of their lobbying or buying power, rather than what they can do with technology, data or services in terms of how they benefit people in the community. This needs to be driven by an impartial organisation – so maybe ISO, NHSX or NHS Digital.

Whatever happens, we mustn’t allow innovation to be throttled or for size to be the decision maker in innovation.

That’s why I’m very much in favour of a fund being established to invest in scaling up proven, small-scale digital technology innovations. There are numerous examples of tech flourishing through the pandemic – but they often need funding and support to grow potential.

The importance of user engagement

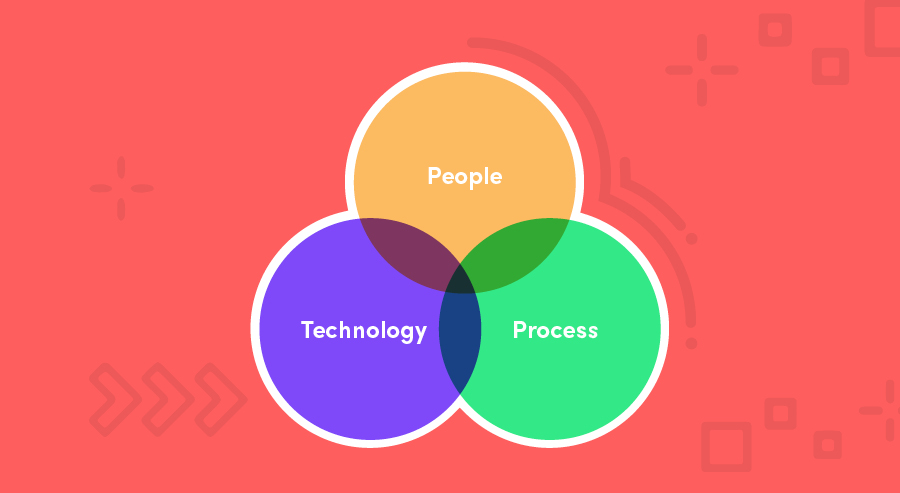

Of course, technology alone will not drive the required change the care sector needs. There’s nothing more confusing and irritating for an employee than change for change’s sake. If the purpose of a new app or piece of software is not apparent, then it already presents a cognitive issue to your team.

Instead, it is the triangulation of people, processes and tools that will drive that the wrong culture easts transformation for breakfast – and only by engaging the intended users of digital technology through the change programme will change be given the maximum opportunity to succeed.

The process of gathering information and insights to underpin your transformation strategy provides a great opportunity to engage with your organisation’s culture. Structured interviews with stakeholders, open and informal workshops, and the opportunity to comment anonymously via online surveys are all excellent ways to stimulate conversations, test ideas and achieve buy-in.

The ultimate goal is to create a burning platform for change, built around a compelling vision that inspires people to take action because they can see that transformation is relevant and beneficial for them too.

Support this by ensuring that your employees have access to reliable information updates and training in a safe environment while they’re adapting to technology in the workplace is the best way to ensure that each employee can really engage with the changes you’re bringing in.

Five key actions to take now

Steve Morgan explains why now is the time to take bold action.

As the world resets following the pandemic, now is unquestionably the time for bold action to transform social care.

The system clearly needs a long-term funding settlement; but above all else an ambitious reform plan that it fit for the future is required. We must commit to a progressive new vision for adult social care, one that delivers a more preventative, asset-based, accessible, co-produced and joined-up system of care and support.

With that in mind, here are five key actions I believe should be taken now in order to power lasting change:

1.Expect and plan for further austerity

We must think of every aspect of the delivery of care, whether that’s from a social care or a health perspective, or a root and branch review of when we spend money on care delivery. Is it the right thing to do? Is the level of spending correct? What is the value associated with what we’re doing for every pound that’s being spent? Do this right and it will drive a fundamental change or shift in thinking. It might sound heartless, but we’ve got to start treating the delivery of care like a business.

2.Introduce creativity to strategic thinking

Mirroring the NHS, this is where you look forward to your five-year plan. If you want to be famous in the world of care, strategically, what would you change? Care is one of those few areas, I think, in the 21st century, where there appears to be little strategic thinking around the continual improvement of service delivery.

3.Mapping the opportunities to bring services together

If you look at the delivery of assessments, you could have a cognitive assessment, a needs assessment and/or a financial assessment, plus a behavioural assessment. Each one of those would be delivered by different, independent bodies. Could we not bring those together and have them delivered by a single individual who is empowered to operate on behalf of those other organisations?

What it comes back to is treating this like a business. In a business, no way would you have four different organisations and four different people ostensibly going out and doing the same thing, at a different time and using a different capability. It’s just waste. You need to drive waste and latency out of the transactions that you’re responsible for.

This is also where joined-up, multi-agency thinking is required. Expanding NHS England and Improvement’s population health management programme, to give local authorities access and capabilities to utilise predictive analytics so that they can better target services at those at most risk.

4.Think prevention, not cure

For future social care to have people at the heart of delivery we need to think about a preventative and proactive approach. After all, preventative investment in social care will deliver benefits to society – more people will stay healthy, happy and independent for as long as possible – and the public purse. Currently, it remains a small proportion of social care expenditure. I think it’s time we changed this.

5.Embrace organisation-wide technology now

The technology that can make a real difference to social care is available now. What’s more, a recent paper from Socitm showed how social workers are more ‘digital ready’ than previously thought, driving the thinking that we’re increasingly seeing at Educatief Software Collectief that more frontline staff need to be engaged in identifying opportunities for digital improvements… not just in improving service management and client outcomes, but in projecting what the future shape of social care could be.

If we invest in scaling up preventative, person-centred approaches to care, including asset-based solutions to reducing social isolation, shared lives and community agents, outcomes can be improved, and costs reduced.

As part of this solution, we need to invest in technology, which had a huge potential to support more people to live independently. Data, workforce and true partnerships, which bring into the equation the necessary and potentially cost-saving collaboration, are critical in delivering the right care at the right time and making real differences for people.